As a hockey parent, your role is far more significant than shuttling your player to and from the rink. You are a critical part of your child’s hockey journey, wearing multiple hats: mentor, cheerleader, logistics coordinator, and sometimes even a therapist. This journey is filled with moments of elation and pride but also comes with its fair share of stress, doubt, and hard decisions. Here’s a closer look at the highs and lows of being a hockey parent and how you can navigate this emotional roller coaster.

The Operational Role

From the very beginning, parents take on significant operational responsibilities. These tasks might seem mundane, but they are the foundation of a player’s success:

- Navigating Tryouts and Politics: Deciding where to play and understanding the nuances of team tryouts can be daunting. Often, you’re not just evaluating your player’s skills but also trying to navigate the political landscape of team selections.

- Choosing Events Wisely: Determining which recruiting events, camps, or showcases to attend can feel overwhelming. Each opportunity has the potential to open doors, but not every event will be the right fit for your player.

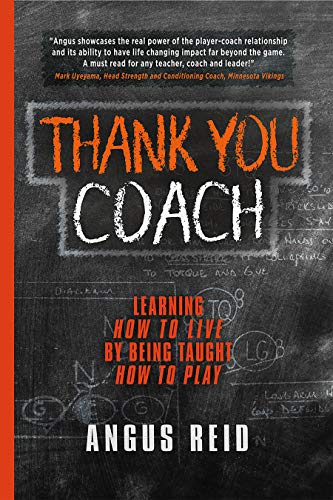

- Finding the Right Coaches: Identifying team coaches and development specialists who will genuinely help your player grow is a critical and sometimes challenging task.

- Managing Logistics: Beyond hockey strategy, there’s the day-to-day grind—getting your player to practices, games, and tournaments while ensuring their gear is in top condition.

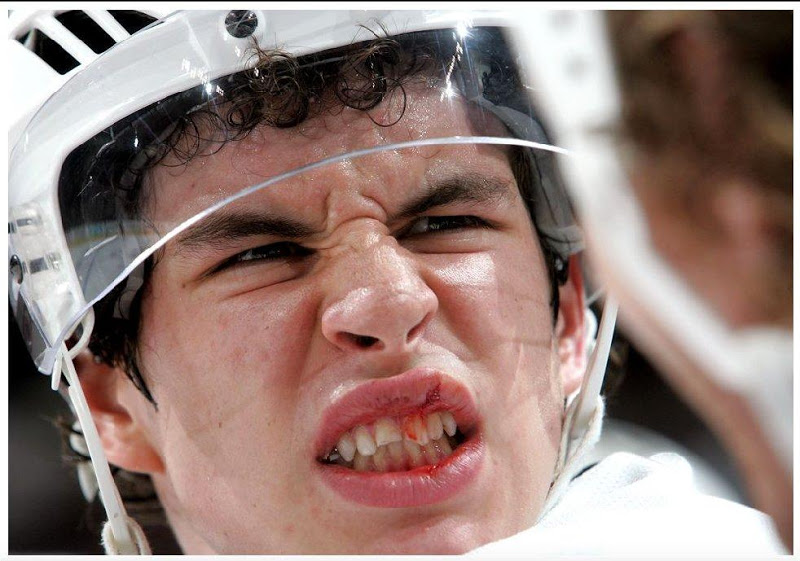

- Overcoming Challenges: Injuries, academic struggles, or even tough situations with teammates or coaches require your steady support and problem-solving skills.

The Emotional Investment

The emotional stakes for hockey parents are high. Every decision feels critical because it’s not just your journey; it’s your child’s dream on the line. Some of the most emotionally taxing moments include:

- Handling Pressure and Rejection: Watching your child face rejection, whether during tryouts or District/Provincial camp selections, can be heartbreaking. The pressure to succeed often feels heavier for parents than for players.

- Deciding Whether to Stay Local or Move Away: Determining if your child should leave home during high school to pursue hockey dreams is a monumental decision. It’s not just about hockey but also about their overall development and happiness.

- Worrying About Making Mistakes: One of the most significant stressors is the fear that a wrong decision on your part might limit your player’s opportunities. This weight can feel overwhelming.

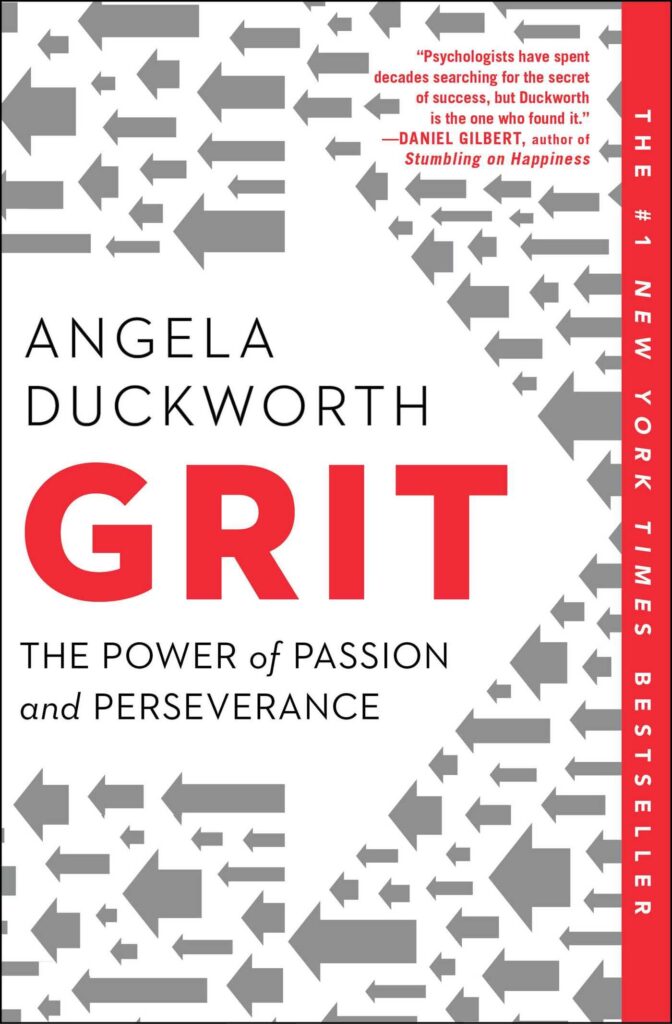

Embracing Imperfection and Learning as You Go

Here’s an important truth: there is no perfect path in hockey recruiting. Even with careful planning, there will be surprises, setbacks, and unexpected opportunities. What matters most is effort and adaptability. By leveraging the resources at your disposal—coaches, fellow parents, online tools, and more—you can minimize missed opportunities and guide your player effectively.

If your player is good enough and truly passionate, doors will open—even if it’s not the door you initially envisioned. Rejections and detours are often temporary. Many players find that what initially seemed like a setback actually led them to a better fit in the long run.

Focus on the Best Fit

In the end, it’s not about landing on the “best” team or achieving every lofty goal; it’s about finding the right fit for your player. The “best fit” means an environment where your player can grow as an athlete and as a person. It might not look exactly like what you initially hoped for, but it often turns out to be just what they need.

Words of Encouragement for Hockey Parents

You are not alone on this journey. Every hockey parent rides the highs of thrilling wins and the lows of difficult losses. The key is to stay grounded and remember why you’re doing this—to support your child’s passion and help them pursue their dreams. Give yourself grace and embrace the learning curve. By showing up, putting in the effort, and making thoughtful decisions, you’re already doing an incredible job.

So, as you navigate the emotional roller coaster of being a hockey parent, take a deep breath and trust the process. It’s not about being perfect; it’s about being present. And more often than not, things have a way of working out in the end.