This past weekend I attended my first USA Hockey Girls District Camp in Las Vegas for the Pacific District with my daughter (2006 birth year). As someone who is new to this whole process, I wanted to share what I learned attending my first USA Hockey Girls District Camp. There were many things I didn’t know or understand until we went through the experience and I had conversations with the organizers & coaches in attendance. Since the Pacific District Camp was one of the first ones to be held in 2021, hopefully there are other players and parents who can take some of this information to help them with their own preparation.

Which players were invited?

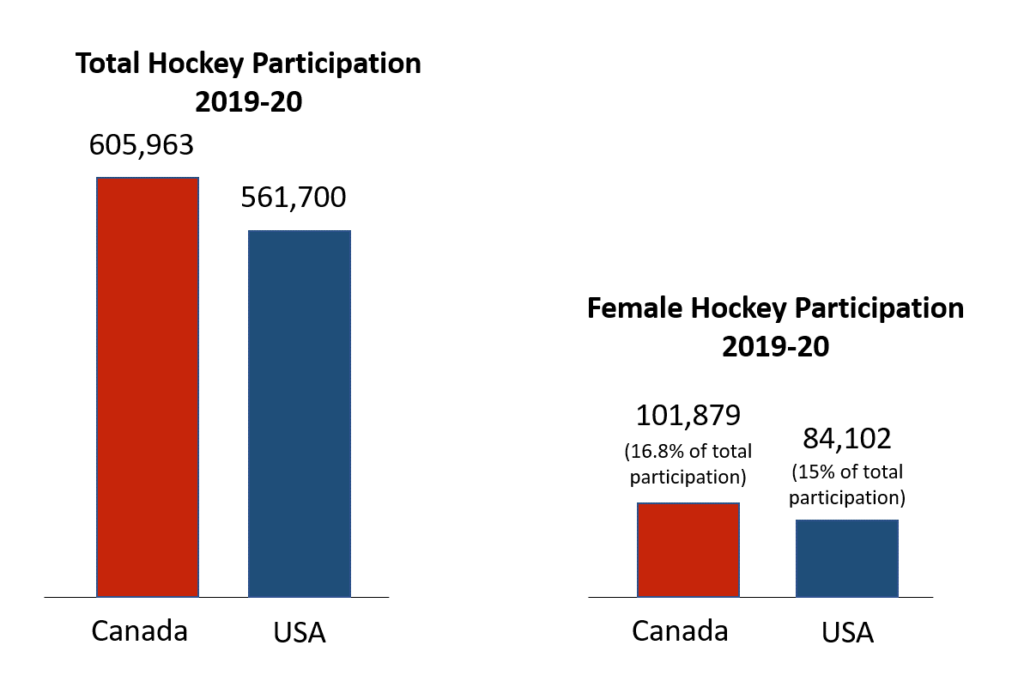

Like all USA Hockey girls district camps, there were two age groups. One for 15 year-olds (2006 birth year) and one for 16- and 17 year-olds (2005, 2004 birth years). The players were selected by their state affiliates (e.g. California, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Alaska) with the numbers of players from each affiliate somewhat in proportion to the # of USA Hockey registration participation level. So, if a state had twice as many female players for an age group, they would be allocated twice as many sports at the district camp.

At each level players were placed on to one of 4 teams comprising of up to 9 Forward, 6 D and 2 Goalies.

What did the players do?

Over the course of the weekend there were 3 on-ice practices, 3 games and 2 off-ice zoom sessions. For goalies there was an additional goalie-specific on-ice sessions at the start of the weekend.

On-Ice practices were run by DIII coaches with assistance from affiliate coaches. These practices were straight out of the USA Hockey ADM practice philosophy which included a 4-station rotation, half ice small area drills & games and of course some cross-ice games with different types of variations of 3-on-3. From my observation, while there was the occasional tip from a coach here and there, there was not a lot of heavy technical feedback, instead the tone was quite positive and focused on giving the girls a lot of reps.

For games, each team played the other 3 teams once. Games consisted of three 22-minute periods of running time, with a break at the 11-minute mark for the 2 goalies on each team to switch and ensure equal playing time. For most games, the scores were not posted on the scoreboard and all penalties were enforced as penalty shots with players chasing down the shooter from behind.

The Zoom calls mainly focused on education players on the college recruiting process and the do’s & don’ts when communicating with college coaches. Many of the same topics that we have covered in the Champs App Podcast were covered in these calls.

PLAYER EVALUATION

Before arriving at the PDC, there was not a lot of information shared about the evaluation process, however I did speak in-depth with Kathy McGarrigle, the Pacific District Girls Hockey Director, who was responsible for organizing the entire weekend (she is also the Founder, Program Director and Head Coach for the Anaheim Lady Ducks). She graciously answered all my questions.

Kathy explained to me that, historically, the Pacific District joined forces with the Rocky Mountain District to have a Multi-District Camp, but with the expected growth in girl’s hockey in Nevada and Washington thanks to the Golden Knights and Kraken, the Pacific District is focusing on having their own camp for the coming years.

Who:

Kathy McGarrigle made it clear to me that all of the evaluators were from outside of the Pacific district to ensure complete objectivity and that process was not political. No one affiliated with a club or program is involved in the decision making. The evaluators consisted of DIII team coaches who were behind the bench and on the ice during games and practices, but several off-ice evaluators who stood in their own blocked-off section away from spectators. Beyond the evaluators for the Pacific District Camp, there were additional USA Hockey evaluators scouting the event for the national camps in July. They were there to see if any 15/16 year-old players were strong enough to be chosen directly for the U18 National camp as well as capture additional information on top players being considered for all the national camps.

There were no DI coaches in attendance likely due to the recruiting blackout period which does not get lifted until June 1st combined with those coaches being more focused on the national camp players (who are most likely to be DI prospects).

What:

While no specific or official guidelines were provided as to what was being evaluated, Kathy mentioned to me all the basics in terms of hockey skills like skating and passing, team play, character and effort. In addition, she emphasized that scoring the most goals didn’t guarantee anything, they were looking at the complete player over the entirety of the weekend.

When:

Evaluators watched all games and practices for the specific age groups they were assigned to (either 2006 or 2004/05). The third and final games were where all the evaluators were together watching the players at the same time. Kathy explained to me that at the end of each day the evaluators convened to discuss the top players and systemically put together a dynamic rank of players which does not get finalized until after the final games on Sunday.

Why:

For the players in attendance at the camp, the ultimate goal is to be selected for one of the three National Player Development Camps taking place this July in Minnesota (15s, 16s/17s and 18U). Once again, the number of spots allotted to the Pacific District is based on the percent of registrants in USA Hockey, of which the Pacific District represents ~6% of the player population. Since the 15s National camp has about 216 players in attendance, then the Pacific District should get ~13 spots (plus or minus) for that age group. For the 16s/17s, those numbers there are the same number of spots, but for both birth years since that camp is combined, thus the number of spots is allocated by birth year in proportion in registration percentage.

Kathy informed me that the final list of invites to the national camp would likely not be released until June 9th, 2021 since the Pacific Camp was one of the first in the country to be completed. As the players who will be invited to the U18 Camp are decided, there is a cascading effect on who will get invited to the 16s/17s camp and is dependent on other districts completing their camps. Thus, the delay of nearly a month until we will are informed on the Pacific selections.

My thoughts:

Overall, the weekend was a great opportunity for the girls to compete with the top players on the west coast and see how they compare. In reality, there was a big standard deviation in talent, but this is something I expected since the Pacific teams tend not to be as strong for girls hockey as other areas of the country. So, hopefully it was a good learning opportunity to benchmark and self-reflect on which part of their game each player needs to work on.

Unfortunately, due to the Covid protocols and the short weekend, no formal feedback was provided to the girls (only ad hoc on-ice or behind-the-bench guidance). As Kathy suggested to me during the weekend, if a player wanted feedback, they should proactively query their coach. That would be my recommendation to players who have upcoming camps in other districts, to ask their coach for their advice on their specific development needs towards the end of the camp.

P.S. A memorable part of the weekend was when a parent from Alaska recognized my Champs hat and asked “Are you the Champs App Podcast guy?” and thanked me for the podcasts.