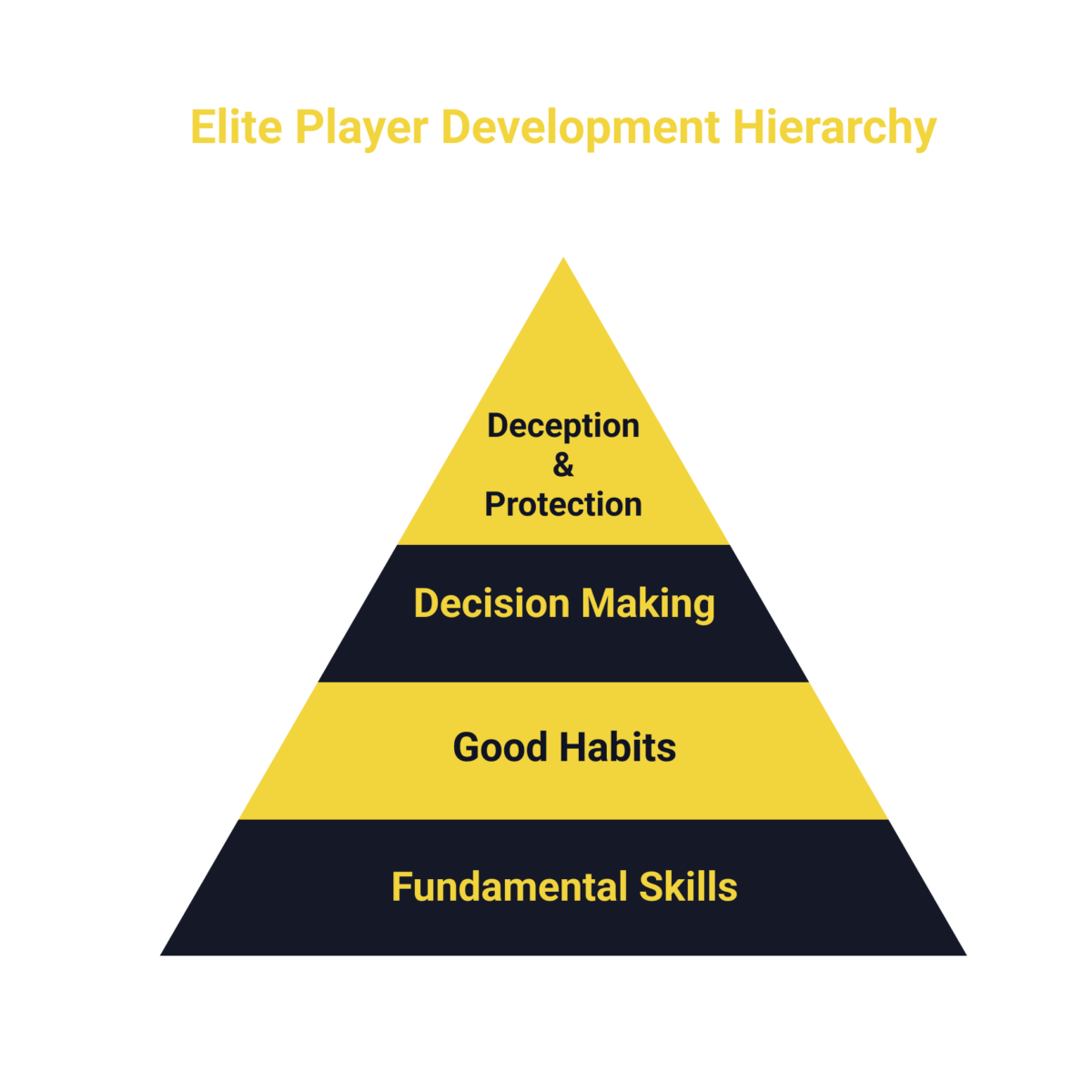

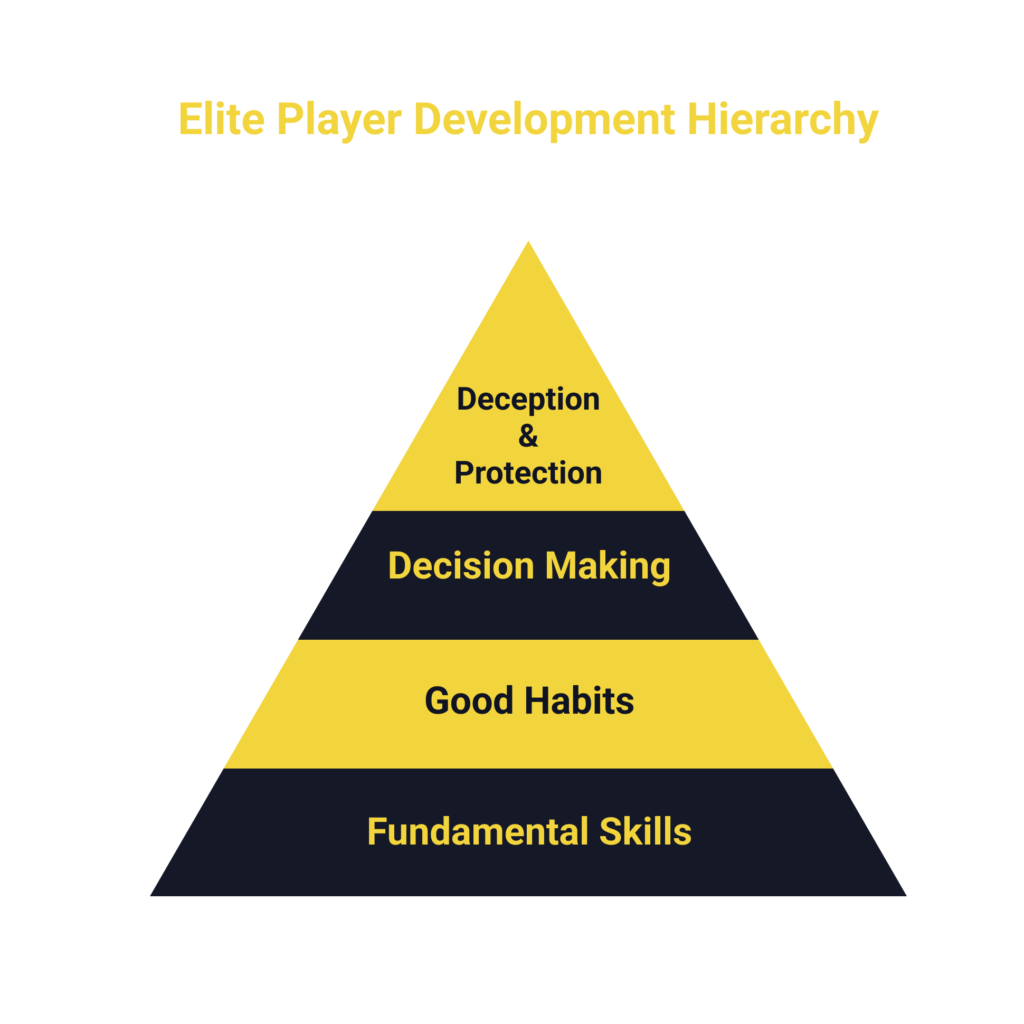

The Player Development Hierarchy

In past posts, I have discussed what it takes to become a great hockey player. To keep it simple, I would say that those posts describe the path to becoming a true AAA-level player. At every age group, there are roughly 150-200 AAA level teams for boys and 75-100 AAA teams for girls across the US and Canada. That means that means there are over 1000 great hockey players at every age level.

So what does a player who is the best-of-the-best look like?

Over the past couple of years I have watched many of the top teams and players on both sides of the border and have come up with a simple framework on the hierarchy of attributes that these top players possess.

The following diagram shows how these attributes build on each other and, when done in combination, display a top-level of excellence in hockey players.

Level 1: Fundamental Skills

Hockey requires a range of fundamental skills, including skating (e.g. speed and agility), stickhandling, shooting and passing. These are the essential capabilities a player must have in order to get to the elite level. Clearly, becoming elite at one of the skills helps get you closer to becoming an overall top-level player, but it isn’t sufficient.

Level 2: Good Habits

There are several on-ice habits that hockey players need to develop and demonstrate on every shift. These include technical behaviors like shoulder-checking and staying between the dots if you are a D. Or sticking with your man or going hard to the net and stopping at the goalie if you are a forward. Quite frankly, for every position there is a long list of good habits a player needs to learn and continually maintain. More broadly, here are some of the other good habits that separate the elite from the rest.

- Hustle: Hockey is a fast-paced game that requires players to move quickly and efficiently. Players who hustle and work hard on the ice are more likely to make plays and create scoring opportunities for their team. Scouts notice which players hustle every shift versus those that take some shifts off during a game.

- Communication: In a game, players need to communicate with their teammates on the ice, using clear and concise language to call for passes, provide direction, and coordinate defensive strategies.

- Positioning: Being in the right place at the right time is critical to elite players. Knowing where and when to move to the right areas of the ice separates top players from the rest of their peers.

- Anticipation: Anticipation is the ability to read the game and predict what will happen next. Players who are able to anticipate their opponents’ movements and read the play effectively are more likely to make plays and create scoring opportunities for their team.

- Discipline: Discipline is important in hockey, both in terms of staying out of the penalty box and maintaining good habits on the ice.

By developing these good on-ice habits, hockey players can have a strong foundation to play at the elite level.

Level 3: Decision Making

To become an elite player, decision making is a critical skill that must be constantly developed and honed. Specifically, decision making spans multiple dimensions and situation for players:

- Reading the Play: Hockey players must be able to read the play and make decisions based on what they see on the ice. This involves being aware of the positions of teammates and opponents, predicting where the puck will go, and anticipating the movements of other players.

- Puck Management: Puck management is an essential aspect of decision making in hockey. Players must decide when to shoot, pass, or carry the puck, and must be able to make those decisions quickly and confidently.

- Positioning: Good positioning is key to making effective decisions in hockey. Players must be able to position themselves in a way that maximizes their effectiveness and allows them to make quick decisions based on the flow of the game.

- Communication: Effective communication is essential for good decision making in hockey. Players must be able to communicate quickly and clearly with their teammates, both on and off the ice, to ensure that everyone is on the same page and can make decisions based on a shared understanding of the game.

- Adaptability: Finally, hockey players must be adaptable and able to make decisions in a fast-paced, dynamic environment. They must be able to react quickly to changes in the game and adjust their decisions accordingly, often on the fly.

Level 4: Deception and Protection

Deception and puck protection are important skills for ice hockey players to develop in order to create scoring opportunities and maintain possession of the puck. In my experience, it is the highest order of development to display, because it relies on all the other attributes for players to be able to successfully perform them during games.

- Deception: Deception is the act of misleading or confusing an opponent in order to gain an advantage. Players can use deception in a variety of ways, such as faking a shot, passing in the opposite direction, or changing direction suddenly. To develop deception skills, players should focus on maintaining good body posture and making quick, decisive movements to keep opponents guessing. There is a long list of fakes, but knowing which one to pick at the right moment is a skill in itself.

- Puck Protection: Puck protection is the ability to maintain possession of the puck while being checked by an opponent. To protect the puck effectively, players should keep their body between the puck and the opponent, use their body to shield the puck (e.g. mohawks or pivot turns), and maintain good balance and body position. They can also use quick fakes and sudden changes of direction to throw off the opponent’s timing.

- Reading the Defense: To be effective at deception and puck protection, players should be able to read the defense and anticipate their opponent’s movements. They should look for gaps in the defense, predict where the opponent is likely to go, and adjust their movements accordingly.

Deception and protection can be high risk, especially if they aren’t executed properly. If players attempt a fake or fancy puck protection move and fail, it can easily end up in the back of your net and you can be stapled to the bench by your coach. This is why players who can successfully perform these moves are considered elite.

It is certainly possible to demonstrate parts of these four attributes independently of the other, but to be a high end AAA player, these capabilities create synergies with each other when performed consistently together.