It’s been over 3 years since Champs launched. Since then we have accomplished some amazing things:

- Offered a free online hockey profile creation tool for players, coaches, parents and advisors/agents

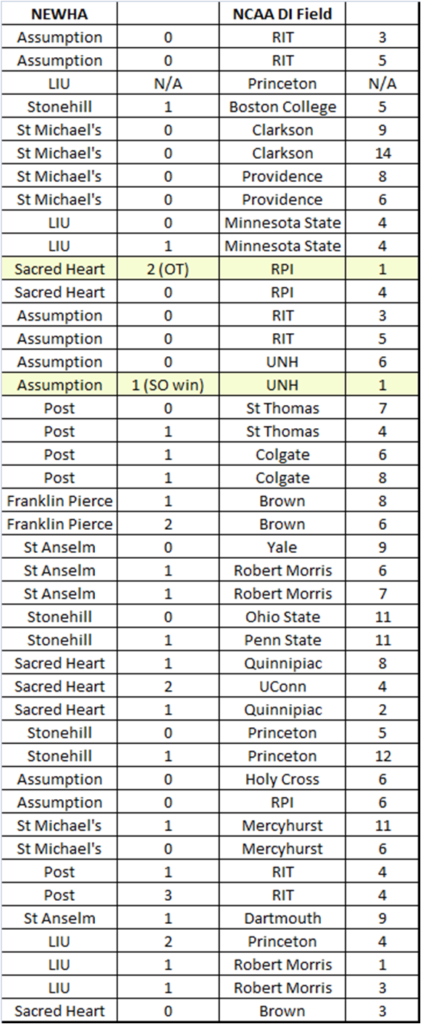

- Provided analysis, insight and opinion on a range of women’s hockey topics including recruiting, development and news.

- Developed several tools to help players, parents and coaches navigate the world of youth hockey

- Interviewed at least one coach from all 45 NCAA DI Women’s Hockey team

Over the past few months, we have spoken to many users and gotten their feedback as to what they like, don’t like and where they want Champs App to go in the future. The positive feedback to what we have accomplished so far has been amazing and we truly appreciate the trust we have earned from our users.

Continued Commitment to our Mission Statement

Recently I have been asked if I will continue my work on Champs App now that my daughter has committed to play college hockey. And the answer is very simple: Yes. Not only am I still helping my son with his recruiting journey, but I am also still passionate about helping improve the recruiting and development your hockey experience for all players. So, plan to see Champs App expand to all youth hockey, not just female hockey, over the coming months.

As a result, our team doubled-down on our commitment to our mission:

“Champs App’s mission is to empower youth athletes to reach their full potential. We serve as your trusted sports recruiting and development copilot, supporting players, parents, and coaches on their journey through youth sports. Our goal is to help you achieve your goals and excel in every aspect of your athletic and academic pursuits.”

New Design

Since our initial launch, many of our solutions have been somewhat independent of each other and somewhat confusing for folks to figure out Champs App. Today we are launching Champs 2.0 which beings together all our offerings in a more integrated solution.

We have completely redesigned Champs App so that all offerings fit together seamlessly to dramatically improve our user experience. Our hope is that it is much easier to find and use Champs App as your copilot.

Changes to our User Experience

You will also see many changes to how users can access and use Champs App 2.0. While we will continue to provide free content and tools like podcasts, articles and directories on our website, some new content will require a free Champs App account to access special analysis and information. We have made it easy to create a free Champs App account, without the need to create an online profile.

Free vs. Subscription Offerings – Focused on Great Value

As mentioned above, Champs App will continue to offer free tools and information, but at the same time we have also started to offer premium tools and services. By charging our community for these value-added services, we can continue to grow and deliver amazing new content, tools and services to our members. Unlike other organizations in youth sports, you can rely on Champs App to be your trusted brand in all aspects of your recruiting and development journey.

I have been a longtime of Costco and their commitment to ensuring great value to all their members. We are hoping to echo that same philosophy here at Champs App. As long as I am running Champs App, our intent is to ensure that that the value our members receive from an offering is significantly greater than the price we charge. Hopefully, our community will quickly discover that Champs App premium offerings are truly great value, especially when compared to paying > $300 for a composite stick. In addition, we will never have traditional advertising on our site. Any partnerships or sponsorships will need to be highly valuable to our community and truly help solve their unmet needs.

Our first premium product has been the Champs App Messaging Tool – which is the fast, easy way to send error-free messages to coaches. Champs App Messaging cuts the time to send emails to coaches by over 50%. Over the coming months we will continue to offer additional premium tools and services to our community.

Stay Tuned – More to Come

There will continue to be small updates we need to make as part of our Champs 2.0 release – so if you have feedback or find something that isn’t working properly please let us know. We still have a long way to go achieve all the big goals we have for Champs App. You will see new offerings being released throughout the spring and summer – so look out for more announcement on social media, in your email and in the app. Please join us on our journey to be your sports recruiting and development copilot.

Ray Tenenbaum, Co-Founder of Champs App