Part II

USA Hockey Player Development

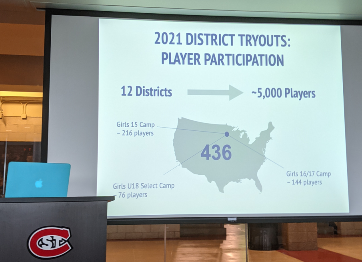

This post is the second in a series about the USA Hockey Girls 15’s Camp I attended from July 10-15, 2021.

At the start of camp, Kristen Wright helped provide perspective on how to think about the bigger picture for what the week was about. The 15’s Camp is really just the first step in a USA Hockey player’s journey at the national level. For many it can be a multi-year process including their college years as the they try to be included in the conversation to make the National Women’s Team.

Realistically, in the short term, for most girls, the ultimate goal of attending any of the girls camps (15,16/18 or U18), is to be invited to the Women’s National Festival which includes players from all age groups (National Team, U23 and U18) being considered for a national roster.

However, for the week of camp, unless something truly exceptional occurred, this Covid year, there would be no decision on advancing or further outcome beyond the camp for any of the players in attendance. Everyone would just head back home richer from the experience and will go though a similar process next year to make the 2022 16/17s camp or if they we one of the top players, potentially go directly to the U18’s camp.

Given the above, what did I think were the objectives for the camp from a USA Hockey perspective?

- Learn about the USA Hockey national program for girls/women and understand what it takes to compete and potentially make a national team (U18, U23, Women’s National Team)

- Get seen & scouted by USA Hockey Coaches (to help get on the radar for the U18 Camp for 2022)

- Get feedback on strengths and development opportunities

- Get a benchmark of how good a player is relative to their peer group

1. Learn about the USA Hockey National Program

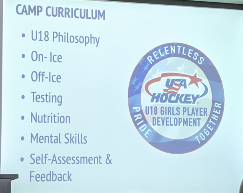

During the parent meeting, Kristen Wright shared the three core values of the USA Hockey program:

- Relentless

- Pride

- Together

And from what I could sense as an outside observer, all the activities for the week centered around these principles. In addition, the theme of the week focused more on helping players be the best they can be rather than solely focus on what it would take to make any of the different age-specific national teams. Given the size of the camp, on balance, that seemed like a more realistic focus. Better to focus on the values that players would need to consistently demonstrate to make a team rather than hockey-specific attributes that may not resonate at this time for most of the girls.

2. Get seen & scouted by USA Hockey Coaches

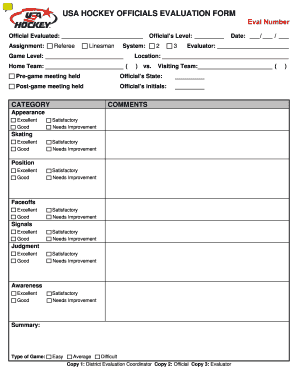

As mentioned in my previous post, the on-ice coach to player ratio was about 1:3 with somewhere in the range of 70-100 USA Hockey representatives participating in the camp. I am assuming that USA Hockey leadership had some type of scouting information collection capability from both on-ice and off-ice observers at both games and practices. In addition, team coaches, team leaders and interns all got to observe their players both at the rink and outside of the rink during the week of camp. Given all these points of data, I would expect that there is some type of player tracking tool with a summary of the information that was collected on each player. There must be some type of report card (beyond the testing results) that was being kept on each player. Ideally, this database would be used to benchmark players if they return to another USA Hockey camp.

As Kristen Wright alluded to the parents on the first afternoon, roughly speaking players are group into A’s (Top 25 or Top 50), B’s (the next ~100) and C’s (the lowest ~75 players). However, the messaging was clear, it really shouldn’t matter right now for players to hear what level they were evaluated. The girls were there to learn about what it took to make it to the next level in USA Hockey and they need to take those learnings and go back and work hard and get better for next year. This year’s evaluations would primarily be used as a way to track development and improvement in a year from now.

3. Get feedback on strengths and development opportunities

Each player received some type of feedback from one of their coaches during the week. Depending on the team and coach, the feedback session occurred during the second half of camp and was a 1-on-1 meeting with one of the two team coaches. Since I was not a player, I could only gather information indirect accounts from players or parents, so my sample size may not be big enough. Evaluation was almost entirely qualitative than quantitative. However, the one consistent theme I heard was that the feedback session wasn’t that great. Comments ranged from advice being too generic (e.g. “go back home work hard, get better and come back and show us what you can do next year”) to not offering any real thoughtful insights to putting the onus on the player to self-evaluate and then mostly agreeing with the player’s evaluation. The consistent theme that I heard was that not enough effort was put into preparing for the feedback session.

In my opinion, this was an area that is an area that the camp could have had a bigger impact.

My personal thoughts are there should be some type of formal feedback process. Ideally with a standardize report card by position (goalie, defense, winger, center). Each player should have received written, detailed feedback on their strengths and key development opportunities (e.g. 3 for each) to help take their game to the next level (which would be personalized to the appropriate for that individual player). I realize this is a tremendous amount of work, requires a lot of coordination between all the coaches and has some pretty significant risks if not properly implemented. And I agree 100% with Kristen Wright the goal is build and maintain player confidence is key. However, given how much players and parents are invested (in every sense of the word) in their hockey development, having some type of tangible, standardized evaluation would be invaluable for these players. To be clear, I thought the week was exceptionally well-run and a great experience for all involved, but this was my one disappointment as a parent.

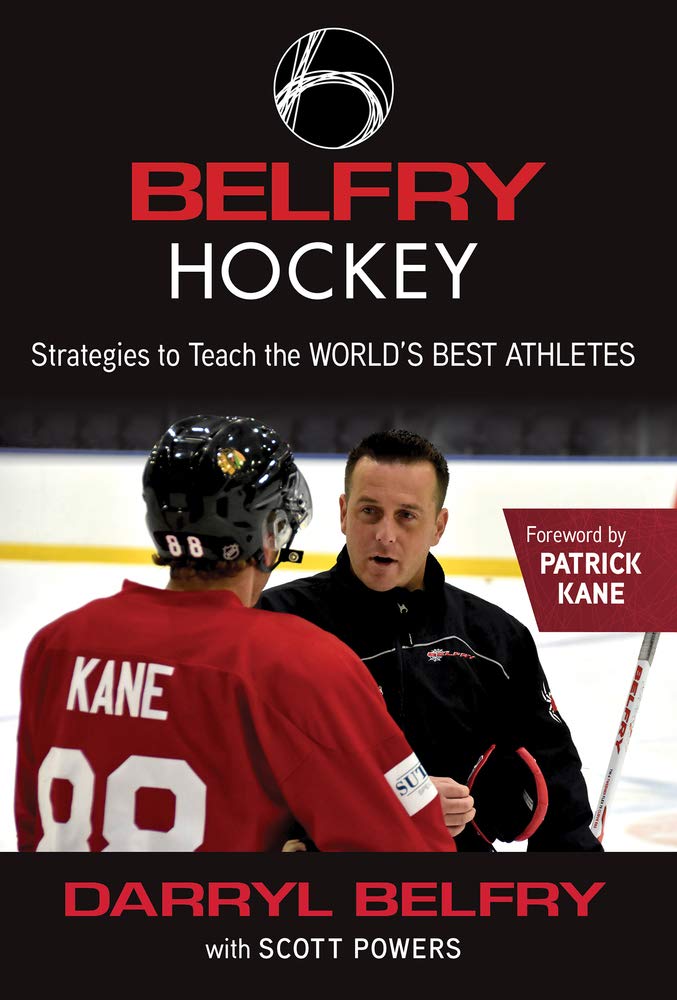

Since we didn’t get that feedback, I ended up doing it myself using footage from the games available via HockeyTV. I’ve started break down the video and comparing them to the top players from the U18 camp who made the National Festival. Most parents probably won’t do this level of video analysis, so there will be a gap in direction for many of the players. It’s disappointing that not all the girls will get a deep dive on their performance.

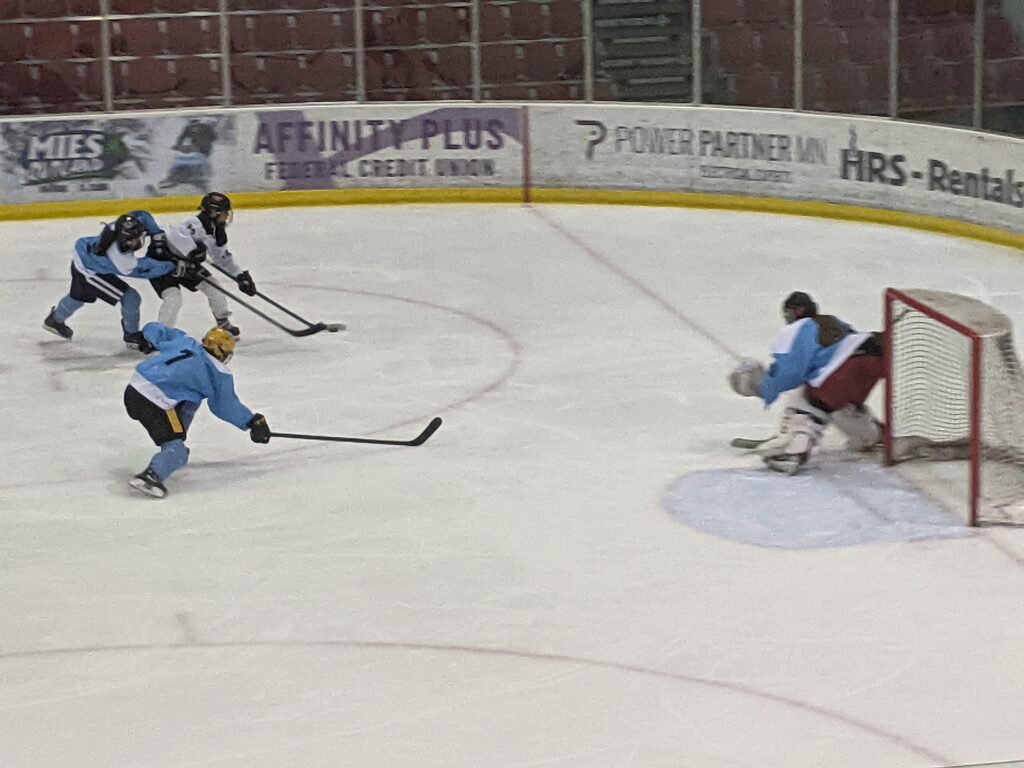

4. Get a benchmark of how good a player is relative to their peer group

My impression was that while the standard deviation at the 15’s Camp was much smaller than at Pacific District camp (where the gap from top to bottom was pretty significant) you could still see big differences from the elite players to some of the marginal players. Depending on the cohesiveness of the team, it was apparent where some players focused more on showcasing their individual talents rather than trusting their teammates and playing as a team. It was great to see multiple passes between teammates being well-executed to create scoring chances. However, in many games missed passes and turnover-after-turnover was occurring on a frequent basis, especially for the first couple of games.

One thing that really stood out to me quite frequently after I saw a player make a great play and I would then look-up where they were from, was how often they were a Minnesota High School player from a school I had never heard of. It was the first time I saw first-hand the high level of players produced by Minnesota hockey on the girls side of things.

In terms of benchmarking, if a player was observant of their teammates, they could pretty easily see which ones were more effective than others (and why). And they could also see the ones who either struggled on the skills side of things (e.g. skating, passing, positional play) or playing a team game. This was on the skater side of things. Since I am no expert on goalies, I am not sure how puck-stoppers would self-evaluate relative to their peers, but hopefully they could see the wide range of styles and abilities that different goalies demonstrated during the goalie-specific sessions.

These were my observations from the USA Hockey U15s girls camp and how I thought it met the objectives for the week from a USA Hockey perspective. While I wished there was a little more direction on the path to USA Hockey success, I fully understand why this is still the top of player funnel from a national team point-of-view.

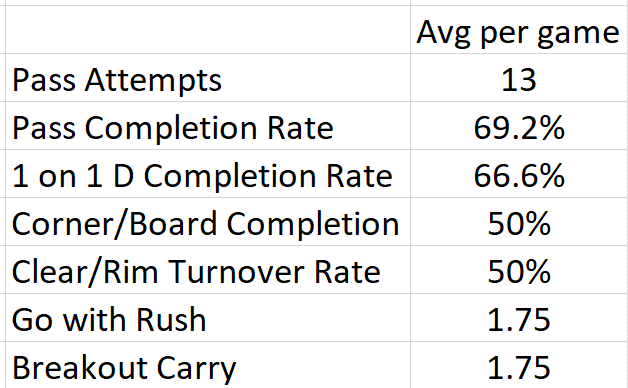

In the final post about the 15s Girls camp, I will discuss the camp from a college recruiting perspective.