Why is ice time important?

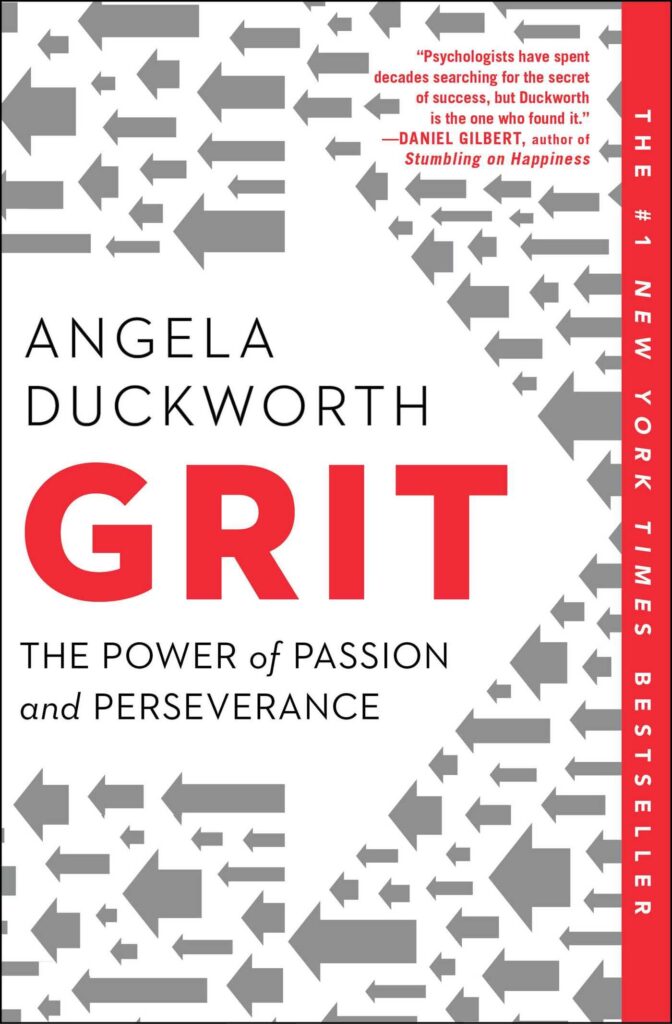

I think every parent and player intuitively believes the more time you spend training on ice the better a player you will be. If you are figuring how to develop a great hockey player, then ice time is at the top of the list. We have all heard the stories of dozens of NHLers who grew up on in small towns in Canada or Minnesota and played on the outdoor rinks or at their local barn for hours and hours until they had to go home for dinner or bed. In addition, if you subscribe to the Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hours theory on domain mastery then being on the ice must be directly correlated to enabling greatness. So that leads to the question, how much time on ice per week should a player need? (Note: this refers to training and development time, not how many minutes of ice time a player has during a game.).

It Starts With Skating

To me the biggest factor to be on the ice and develop into a great player is to become a better skater. Skating is the most important skill to play hockey. If you can’t skate, you can’t play. So, do you need to be the best or fastest skater on the team? No. But you to be a great player you should be in the top 25% of your peer group. Otherwise how can you keep up with the other players who are also striving to be great? Skating is a technical skill that can primarily only be improved with proper coaching and ice time to practice what a player needs to work on.

How Much Time on Ice?

While it would be great if ice time were free everywhere in North America and kids could get their playtime by just walking down the street or out into the backyard to get some independent ice time, the reality is that for most kids this isn’t possible. For many, ice time can be pretty expensive and difficult to access. Given all the innovations and scientific insights about hockey that have arisen over the last 20 years, there must be some optimized balance for players today to get a good bang-for-the-buck for limited ice time that is available to them.

In my humble opinion, you clearly need at least 7 hours per week (averaging one hour per day) at a minimum. Show me someone who is on the ice less than 7 hours per week when they are 11 or older, and I’ll show you someone who is not on pace to be a “great player”. Personally, I believe the sweet spot is more likely in the 10-15 hours per week. Of course you need to balance those hours between focused development and playing/fun (where development is just a positive by-product). Based on all the USA Hockey and experts guidelines, my guess it should be in the 3:1 development to fun ratio.

Expensive vs. Cheap Ice Time

Indoor ice costs money almost everywhere (unless you live in Warroad, Minnesota). Here are some ideas we’ve used to try and dollar average the cost of ice time from most expensive to free to getting paid:

- Private and semi-private skills and power skating lessons (most expensive ice time)

- Hockey camps

- Team Practices

- Rink-run pick-up games

- Skate and Shoot sessions (aka Stick time, Gretzky hour etc.) – only good if scrimmage or have someone pushing them to work on something skill-related. (Too many times I just see kids aged 10-14 just line up at the blue line taking breakaway shots on a goalie. That is working on a skill you may only use once in a blue moon.)

- If you live in a cold winter climate, obviously well-maintained outdoor rinks are superb

- Public skating (Note: our kids get free admission to their rink for public skates as part of their full-season hockey fees)

- Find a goalie coach and offer to shoot on their students during their lesson

- Volunteer as an assistant coach for younger age groups than your own

- Referee (get paid to skate and watch hockey)

Be Coach-Friendly to Find Extra Ice Time

No one is saying you need to be like Auston Matthews’ mom and get a job at a rink so your child can get unlimited access to the rink and play as much hockey as possible. However, if you are creative you can find extra ice time. One of best ways we have dollar-averaged our cost of hockey was to ensure we had good relationships with most of the coaches at our rink, so my kids would often get invited to other team’s practices when they needed players or my kids showed up early (or were asked to stay late).

What about off-ice?

I am firm believer in the Long Term Athlete Development model. Kids should be doing hockey-related strength and conditioning, plus hockey-specific dryland training like stickhandling and shooting. But playing other sports, especially complementary ones like lacrosse, tennis and basketball has multiple benefits back to hockey. For my kids, now that they are teenagers they have slowly narrowed the number of sports and reduced their time spent on other sports, but my kids still play at least one additional sport to hockey every season (e.g. soccer, baseball, pickle ball, lacrosse etc.).

Skating On Lots of Ice

Bottom line, if you aren’t playing working enough on the inputs, the outputs can’t be great. On-ice training somewhere between 7 and 15 hours per week should be sufficient to become a top skater.

This post is the third in a series on How to Develop a Great Hockey Player (Intro).